12:45 P.M. Friday, 15 February, 1991

The Cabin Tavern, Richmond Beach, WA.

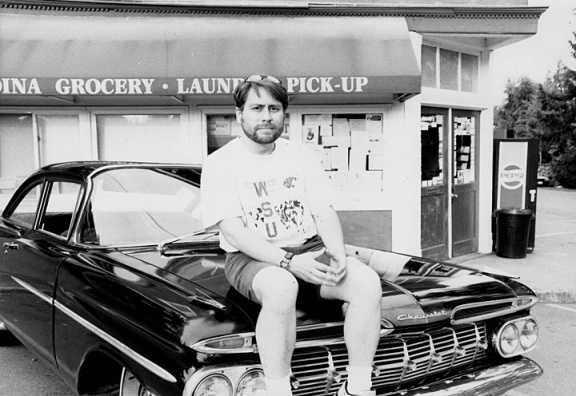

“I was really trying to clean things up, you know? But they just didn’t understand what was going on.” Malach poured another shot glass of beer out of the bottle of Rainier that Reggie had placed on the counter, next to the popcorn and peanuts. “Those assholes. They were just as bad as me. How could they do it?”

Reggie lit a smoke and shook his head from behind the bar. “Malach, I don’t get it. You mean to tell me that they fired you because you quit drinking?”

“That’s exactly what happened. Three months ago, I realized that I wasn’t doing my job too well anymore. So I checked in to detox, and succeeded in getting off the booze…for a while anyway.” He poured another shot of beer and drank it down, a curious habit he had picked up in the Army. “They fired me. Can you believe that shit? They got rid of me because I started doing a better job than everybody else. Fuckin’ alcoholics felt threatened by my new work style.” He poured another shot.

“Man, that don’t seem like much reason to fire someone. I say you’re better off without them.”

“Yeah, but Reggie, I’m 52 years old. I’ve been working at Wesco South for 27 years. What sort of job can a guy like me expect to get at this age? The company has taken the best years of my life and now I don’t have anything left. Everything’s just going down the toilet. I can’t even get Nicole to let me see the kids. I miss them alot, and now for some fucked up reason I miss Nicole too.”

“Shit; you must really feel bad if you wanna see her, Stan.” Reggie put his cigarette butt in a half-empty beer bottle. He had known Stan Malach for 14 years and had never seen him this down. Of course, about the only way that he did remember Stan was sloshed and hanging onto the bar for support; Stan was a good customer for many years. Unfortunately, Stan lost his wife and kids for being a good customer. And now he was losing the rest of his life because he was no longer a good customer. Life had a tendency towards the cruel. “Well, what do you think you’re going to do, now that you don’t have to work tomorrow?”

Malach swallowed another shot. “I going to start by finishing this bottle, and I’m going to finish by starting another one…”

1:15 P.M. Friday 15 February, 1991

18110 Ashworth Avenue North, Seattle, WA.

Clem threw the last suitcase into the back of his pickup. “Bitch, you can’t accept anything! Well, accept this. Our marriage is over. Me and Dinelle are headed for Westport and you can’t stop us.”

Stacy had tears in her eyes. “Clem, you can’t leave. What about our daughter? What sort of life do you think she’ll have when she finds out that her own father ran off with a seventeen-year-old high school drop-out? Don’t you think that’ll give her an awful bad view of you? Our marriage is supposed to be forever, not for as long as it’s convenient. Can’t we work something out? I just want what’s best for the both of us.”

“Well, I don’t give a shit what happens to you anymore. That means I’m leaving you for Dinelle and heading for her Dad’s lumber company. You should have seen it coming, Stacy. You’re too restrictive. You’re always wanting to do stuff with my money like pay those stupid doctor bills. I’ve never seen a baby that gets so sick in my life. It’s not my kid if it’s always getting sick like that. So I’m saying goodbye to you and that sick little crying skinball to live a better life somewhere else.” He hopped in the truck and tore down the street, leaving Stacy with more than tears in her eyes. He left her with a mortgage, a daughter with asthma, a twenty-year-old Dodge, and an empty checking account. All Stacy could do is sit on the porch chair, curl up, and weep in silence. Her life had never looked so bad, and she could see no positive ways out of her situation.

But deep down she knew that Clem really wasn’t the right man for her. She could tell that when the first doctor bill had been due for two months, and Clem bought a dirt bike. If only she had been able to see that side of him when they were eighteen and horny. At the time, it seemed as if their marriage would work, but as the years crawled by, Clem had proven himself to be selfish and undependable. Even so, she was willing to accept a little sacrifice for the sake of her daughter. Kaile deserved a family background. Stacy didn’t want to explain to her someday that her father had left both of them behind out of sheer selfishness, but she knew that the day would come to tell her the terrifying truth, that she was kin to a dickhead with a rubber neck.

As the clock in the house struck two, she decided that it was time to check on her sleeping daughter and call her mother. What else was she going to do?…

2:15 P.M.

Almost finished with his fifth bottle of beer shots, Malach was starting to get drunk, as if he was under the influence of a self-induced anesthesia. The words to “Misty Mountain Hop” rolled off his lips in a smooth slur, caused by the beer that had passed down his throat over the last two hours. He couldn’t remember getting so drunk from five bottles of beer. In fact, he had difficulty remembering catching a buzz off six or seven. In three months, his tolerance to alcohol had disappeared. He drunkenly justified to himself out loud that “rehab has made it cheaper to get wasted.”

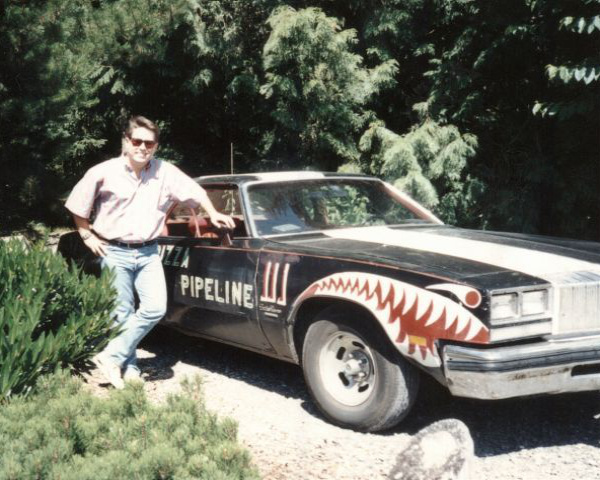

Cross-eyed, he looked around the bar to see the two Reggies walking in parallel behind the two bars. Two men, identically dressed, were playing solo games of pool at two matching tables. He looked outside to see his two cars sitting in front of the bar. He knew that he should go home and sober up, but wasn’t sure if he could negotiate the two sets of lanes going east towards his two homes. Better have one more, he said to himself, because there’s no booze at the house. He took another shot. The feeling in his throat was so familiar and welcome; he never wanted to go back to reality again. Reality is what fucked him over, and he felt better avoiding it. He had missed beer over the preceding months. Often, beer was the only one that could make him feel good. Beer was always there. Beer always listened to his problems, something Nicole quit doing about the time that Malach really needed reassurance. The emptier the bottles became, the more room they had inside to listen. As soon as the empty bottle of Rainier turned into the two empty bottles right in front of his drunken double vision, Malach knew it was time to go.

He stumbled out the door to his awaiting blurry car. He dropped into the driver’s seat like a lead ball and sat fumbling his keys for several minutes. “This is the best part,” he mumbled. “I love this drive home.” Home was six miles east, a drive that Malach had made F.U.B.A.R. many times. After the last bottle, he now had the confidence he could do it one more time. He pulled away from The Cabin and headed east towards North City…

2:25 P.M.

“Yes, he’s gone for good, Mom. He left with that sleazy little Dinelle about an hour ago.”

“Well, it’s about goddamn time. I never liked him anyway. He was almost as worthless as your real father.”

“Come on, Mom, he wasn’t that bad, was he? I mean I’ve only seen my Dad about ten times since I was twelve, but he seemed like a nice guy.”

“He was a lazy, worthless man. But the thing that bugged me about James the most is that he would sit in front of the TV and clean and cut his toenails while I was eating. Imagine that while you’re trying to eat a turkey pot pie. He didn’t give a damn about what was going on around him. Do you realize that he ran out on his child support during the last two years?”

Stacy was experiencing deja vous. Her real father sounded just like Clem. It was a good thing that her mother had found a boyfriend not long after her Dad left town. “How come you and Ray never told me?”

“Honey, when Ray was alive, he loved you more than James ever did. When the payments stopped, he was more than willing to take care of you himself. We both felt it was best. He hated Clem; I want you to know that. You meant more to him than anything. He saw Clem taking advantage of you all along, but was afraid to say something and hurt your feelings.”

Stacy was crying again. “Mom, I miss Ray. He meant a lot to me too. I wish he was around to help me raise Kaile. All I want is for her to have a family life. She deserves that.”

“Well, Stacy, it’s time that you and I do that together. I miss Ray too, honey, but the two of us can raise Kaile just fine.”

The line was silent for a few seconds. “Do you want my opinion, Stacy?”

“Uh-huh.”

“I say you get out of that rat trap home of yours and move back to Edmonds. You know I have lots of space. You can go back to college, honey. We’ll work it out.”

“Mom, I don’t have any money to go back. And what do I do about Kaile?”

“Now don’t you worry about either one of those. They’re both taken care of. You just come home, Stacy; it’s never too late to start over.”

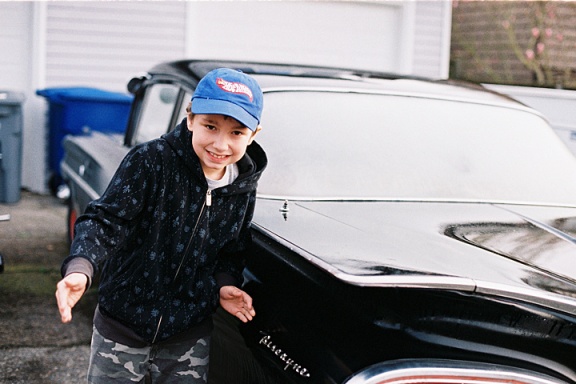

Stacy hung up the phone, and went to check on Kaile. She was sleeping soundly in her crib. Stacy stood and looked at her for some time. She was so adorable in her innocent youth, sleeping as if there were no cares in the world. Stacy thanked God that Kaile looked nothing like her father; to go through life looking at someone resembling Clem would be painful. But now he was out of her life and was never coming back. For the first time she was beginning to feel relief that he was gone, and looked forward to taking another crack at college. She could now see light at the end of the tunnel. Together with her mother, she would raise Kaile to respect independance but not abuse it. With Clem gone, this would be so much easier.

She started packing a batch of belongings that was going to her mother’s. Kaile’s clothes and toys of course went first…

2:30 P.M.

“I can’t believe I’m lost,” mumbled Malach. “How did I get on this street?” He maneuvered his Chrysler through a noisy U-turn at the end of the cul-de-sac and rumbled down the street, attempting to regain his bearings. The last two bottles of Rainier were now starting to take effect, and he began to feel sick to his stomach.

He pulled into a church parking lot, and fell out of his seat onto the grass in front. He looked up to see a carved wooden angel perched on the church’s sign.

“Forgive me father, for I have…HERRRRAALLLPHFFFF!!!!” He strained against the heaves that turned his insides out, breathing furiously between attacks. The convulsions made his back hurt, and his already sour stomach hurt even more. Finally, it was over, with the car still running and Malach curled into a fetal position on the grass. He lay there for what seemed like hours, and started to cry. “Oh God, what have I done? Is my life so shitty that I have to lose out on whatever’s important to me? Why is my worn out body still around?” As he cried out for solace, the angel just stood and watched. A light rain began to fall, creating tears on her face. Nature seemed to be looking on him with an all-knowing eye of sadness, and as the rain came harder, the angel looked more and more despondent over his pain. Malach crawled back to his car and got in. He sat in the seat, drenched from rain and tears, whimpering for salvation.

“Please, God, if there’s justice in this world, I won’t see tomorrow.” He put his car into gear and headed for the intersection of 185th and Aurora…

2:35 P.M.

Stacy packed the back seat up with clothing and toys after strapping Kaile into the car seat. Even though her car was twenty years old, it had her husband beat for dependability. Her Dodge was a relic of mammoth proportions, big and safe. The one thing that Stacy always liked about the car was that it had so much room to pack things. Three or four trips to her mother’s and she would be moved out of her house. The furniture stayed; it was disgusting and old. Whoever bought the house could do with it as they pleased.

“Okay, Kaile, we’re on our way.” Kaile’s laughing grey eyes gave Stacy reason to smile back and kiss her on the cheek. “You’re the best thing I’ve got, Skeeter. You and I are going to Grandma’s–for good.” Stacy strapped herself into the Dodge, pulled out of the driveway with her first load, and headed north to Aurora and 185th…

2:37 P.M.

The intersections were melting away for Malach. To him, the world was one big beautiful blur. The street signs and lights moved by him in an almost surreal fashion, surging toward the back of his car. He tried to concentrate on the road, but kept losing his train of thought as he passed trees, driveways, and anything that would catch his eye in a weird way. He looked at the speedometer. Does that say 10 or 70? He couldn’t tell. Ones and sevens looked the same to him at this point of intoxication. “Whatever speed it is,” he thought to himself, “it doesn’t matter. I haven’t felt so free since the last time I was at The Cabin. Nothing can stop this feeling now.” As his Chrysler screamed down 185th at 70 mph, he could feel all his worries and troubles being magically wiped away. His sudden feeling of freedom was engulfing all his senses. He could see the intersection with Aurora coming up on him fast and blurred.

“Is that light green or is it red…?”

2:37 P.M.

Friday. This was the day that rush hour began early for commuters on Aurora. Stacy was able to squeeze in behind another car going north as she pulled out onto the road. She had always been amazed at the amount of traffic that built up on this street on Friday, as if everyone was just out goofing around. She started to move with traffic as the car in front of her moved forward. It had moved well ahead of her and left quite a gap between them. Rather than move up right behind, she maintained her distance, thinking of safety and speed.

Passing through the intersection of Aurora and 185th, she looked around at traffic conditions. She saw nothing out of the ordinary, until the last second. Barreling down on her from Richmond Beach was a giant Chrysler, doing well over the legal speed limit, and apparently not seeing the red light he was about to run. She screamed in mortal fear and slammed on her brakes.

But the roadway was wet, and her reaction was too late for her car to be missed…

MOTORIST KILLED IN NORTHEND ACCIDENT

Stan Malach, 52, of North City, died in a two car accident yesterday. Uninjured in the accident were Stacy Bonnaham, 22, and her daughter Kaile, 2, both of Edmonds.

Mr. Malach was reported to have run a red light while traveling east through the intersection of North 185th and Aurora at a high rate of speed. According to witnesses, he impacted with the front end of Ms. Bonnaham’s northbound car before overturning into a telephone pole. King County Police are investigating the possibility that Mr. Malach was driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

Ms. Bonnaham and her daughter were treated for minor cuts and bruises at Stevens Medical Center and released.

————————————————–

Written in 1991 as a college assignment – ed.